Photo Source: U.S. National Archive and Records Administration

Fear and the Fifth Column: Political Violence in the Two Koreas

by Haitong Du

August 27th, 2020

The clash of Communism and Capitalism was the theme of the Cold War era, during which brutal civil wars between the two ideologies arose on all major continents, many of which are often accompanied by mass atrocities. Through analyzing the geopolitical implications of the partitioning of Korea, this article examines how a political border drawn by the United States and the Soviet Union resulted in mass killings by both governments on the Korean Peninsula.

Maj. Gen. Charles A. Willoughby, the Chief of Intelligence of the U.S. Army during the Korean War, once considered Spanish Caudillo and Generalissimo Francisco Franco “a great hero.” The rebel Spain under the control of the Generalissimo was constantly terrified of, and executed en masse, the ideological adversaries suspected of dismantling the nationalist war effort from within. The Spanish Civil War, unfortunately, was not the last time when paranoid leaders sought to commit mass atrocities against their own people in the name of regime security.

“When 50 million South Koreans live in freedom… in stark contrast to the repression and poverty of the North,” former President Barack Obama claimed in 2013 when speaking to the group of Korean War veterans, “[the War] was a victory.” The remark by the former president captures both the divides, practical and ideological, between the two Korean regimes today but also the immense difference between the region now, after over a half century of human history, and what it was before the conflict broke out. In a bloody war for unification, which later drew in American and Chinese soldiers, the conflict between the two Cold War ideologies took the lives of at least three million Korean civilians. What has remained particularly shocking about the atrocities committed against citizens during the conflict was that they were civil, rather than militaristic; both the regime in Seoul and its counterpart in Pyongyang were doing it to their “own” people. These mass atrocities did not target national, ethnic, racial, or religious groups as categorized by the United Nations Genocide Convention; rather, they intended to “purify” the country from the political insecurity brought in by the opposing ideology on the other side of the Korean Peninsula. Furthermore, since the ideological conflict on an international level did not neatly map itself on the Peninsula before the drawing of the 38th parallel, this North-South political divide was very much an external invention. This geographization of political differences inevitably created rationales of massacres in the names of ideological purification and regime security on both sides, leading to mass atrocities such as the Bodo Yeonmaeng Massacre and the Seoul National University Hospital Massacre.

The history of the Korean division is key to understanding where and how the mass atrocities originated. Since the beginning of the 20th century, Korea was a colony of the Empire of Japan, whose occupation came to an end following the conclusion of the Second World War. At the very moment of liberation, however, Korea was once again sacrificed by its great power allies. In the August of 1945, days after the dropping of the atom bombs in Japan, top military officials in the United States held a series of State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee meetings at the Pentagon, discussing the feasibility to safeguard American interest in the Far East, including deterring a Soviet occupation of the entire Korean Peninsula. The responsibility of partitioning Korea into a Soviet zone and an American zone was eventually delegated to a young staff officer named Dean Rusk, who was ordered by his superiors to draft a plan that could “satisfy both the Soviets and the Americans” in 30 minutes. The interest of the Korean people, on the other hand, was not any policymaker’s priority, at least no one with decision-making power in the late Summer of 1945.

"Anger has its roots in fear"

(Helen Graham)

Secretary of State Dean Rusk at a Cabinet Meeting, 16 September 1968

Source: Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library

Staring at a blank map of the Korean Peninsula and running out of time, Rusk drew a straight line with a ruler and a red pencil right in the middle of Korea as the proposal partition plan. The line, aligning with the 38th parallel north and dividing the Peninsula perfectly in half, was later accepted by Washington and Moscow as the official border between their spheres of influence.

Maps of Korea: Blank vs Straight Line

Source: Onero Institute

“When you solve a problem,” Rusk said, “you ought to thank God and go on to the next one.” And go onto the next one he did—more than a decade later, Rusk was named as the Secretary of State by John F. Kennedy, courtesy of his early policymaking experiences in the State Department’s Bureau of Far East Affairs. Hence, a young American who did not speak a word of Korean and had never been to Korea, with his largely ignorant and irresponsible approach to “problem-solving,” laid down the foundation for mass atrocities on the Peninsula.

.jpg)

The 38th Parallel marked by ROK Troops

Source: U.S. Department of Defense

While the majority of the atrocities that plagued the Korean Peninsula were contained within the first half of the 1950s, the term characterizing the violence, “politicide,” was not derived until 1988. This concept, however, was far from new. During the Spanish Civil War, both the rebels under the Franco dictatorship and the supposedly democratic Republicans engaged in mass killings against their enemies, with or without a uniform. In an effort to root out potential collaborators in the city, the Republican government of the besieged Madrid executed most political prisoners, whom the Republicans referred to as the “Fifth Column,” in addition to the four advancing Nationalist columns.

Two decades after the fall of the Spanish Republic, ideological differences only became more destructive on the Korean Peninsula, amplified by the Peninsula's history and the emergence of the 38th Parallel. The paranoia of Republican Spain was shared by both sides of the Korean War: Kim Il-sung’s Korean People’s Army (KPA) frequently murdered civilians with alleged ties to the West, including the massacre of 700-900 medical workers and patients when it occupied the Seoul National University Hospital, worrying about the resistance of wounded POWs. On the other hand, atrocities under Syngman Rhee’s regime in the South were more systematically organized and profoundly more fatal. Months before the Korean War broke out, Rhee ordered the arrest of tens of thousands of suspected communists and “traitors” and enrolled them in the Gukmin Bodo Yeonmaeng (National Protection and Guidance League) for ideological purification. The moment the KPA launched the attack, South Korean police executed all the suspects in their custody. This mass execution, later known as the Bodo Yeonmaeng Massacre, took away the lives of at least 100,000 civilians, many of whom had little to no connection with the communist cause. Due to the racial and ethnic homogeneity of the Korean Peninsula, such horrifying scale of politicide showed that ideological difference can be the only animus for mass atrocities.

Source: U.S. National Archives

The faulty border aligning the 38th Parallel under Dean Rusk’s pencil introduced the idea of geographic division based on ideologies to the Peninsula, where the actual distribution of communists and capitalists was not reflected by this external imposition. The headquarters of the Korean Communist Party was awkwardly located at Seoul, the largest city and the proposed capital for the capitalist regime in the South. The northern half of Korea, on the other hand, had only an obscure presence of communist activities, most of which was unknown to the Soviets. In other words, the geographization of a communist-capitalist border on the 38th Parallel was a proposal nowhere near being grounded in reality. Struggling to find someone that could represent their interest and ideology, the Soviets found their candidate for the Korean leader from the Korean exile community in Russia: a Red Army guerrilla, Kim Il-sung, who resisted Japanese occupation along his Soviet comrades, and was a trustworthy individual in the mind of Joseph Stalin.

Kim Il-sung’s credentials as a Red Army soldier.

Source: Elena Tityaeva

Despite his unimpeachable reputation among anti-Japanese resistance fighters, Kim was virtually unknown in Seoul or the rest of Korea. Months after, with an immense amount of Soviet technical and political support, Kim finished constructing the nucleus of a North Korean government on the previously less communist half of the Peninsula. His government was heavily staffed by bilingual Soviet-Koreans, as well as Korean communists returning from China. As members of the Korean Communist Party fled to the North from Seoul, Kim’s authority and legitimacy was once again challenged by his fellow countrymen. As a result, the North Korean government under Kim was not a monolith. He needed to consolidate power to assert his leadership, and the most natural way to do this was to gain support from the rural population, which made up the majority of the nation.

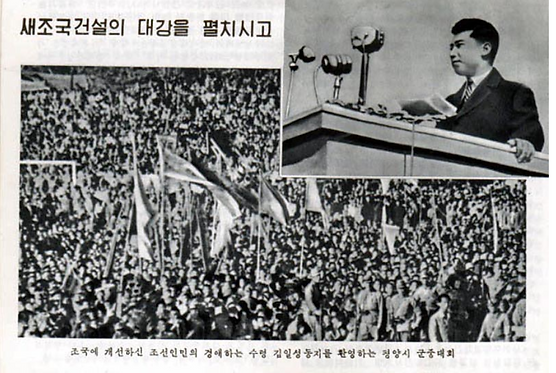

Kim Il-sung Presenting The New Country’s Foundation Outline

Source: Young Suh Kim, Professor of Physics at the University of Maryland

Kim was key to sharpening the political divide that set the stage for the mass atrocities under his watch. By initiating land reform, killing landlords, Christians, and other benefactors under Japanese occupation and seizing their properties, Kim acquired assets from the proposed enemies of his movement and distributed them to his 700 thousand supporters, thus cementing his rule. By emphasizing the class struggle, often at the price of repressing the “enemies from within,” Kim successfully mobilized troops and rallied the peasants under his red flag, prepared to unify the Peninsula and remove the class enemies in the South, too. Kim and his comrades-in-arms perceived their counterparts in South Korea as no longer their “own” people. Quite the opposite, South Koreans were labeled as extensions of foreign interests that threatened the Korean nation:

"The forces of our people are great and their aspiration for unity and independence is unshakable. Neither the bayonets of Syngman Rhee’s bands, nor the threats of the foreign imperialists can stop them. Korea shall be united and independent."

Subsequently, while Rusk, in his 30 minute frenzy, succeeded in separating Korea, he also laid the groundwork for the North Korean politicides, which Kim would frame as an assault on a foreign threat, rather than a move to assert greater political authority. In addition to removing Korean political enemies, Kim saw himself as shaping the character of his nation by “removing a category of people who could never be a legitimate part of it,” in this case, the South Koreans who did not identify with him.

Kim's Attack: The Busan Encirclement

Source: Onero Institute

In an effort to unite the nation under his banner, Kim Il-sung launched an attack against the South in the early dawn of 25 June, 1950. The KPA rapidly captured Seoul, the Southern capital near the 38th Parallel, and rooted out resistance in the city with brute force. Although Kim explicitly prohibited civilian killings because he needed the support from the masses, tragedies were inevitable when wartime imperatives blurred the minds of frontline combatants. Three days after the war began, the KPA captured the Seoul National University Hospital, where approximately 1,000 South Korean soldiers were receiving treatment. One such act of extreme violence saw the KPA set the hospital on fire and gun down around 900 wounded enemy soldiers, doctors, nurses, and other civilians. This massacre demonstrated the danger of politicides: even if they were designed to kill class enemies, they could also target civilians who were loosely affiliated with the “enemies,” such as doctors and patients in the same hospital. Sadly, this was neither an exception, nor was it corrected, as the KPA also killed many innocent children and women who shared the same households with suspected rightists, with or without the consent of the government in Pyongyang.

The memorial of unknown freedom fighters at the Seoul National University Hospital

Photo by: Yong Joo Park

Comparatively, mass killings initiated by Kim Il-sung’s political indoctrination were, nevertheless, dwarfed by atrocities committed by the South. The establishment of the Republic of Korea (ROK) was very much dictated by American policymakers, who did not trust the indigenous political organizations for their suspected communist ties. Conservative landowners, businessmen, and former Korean officials in the Japanese colonial regime, witnessed the situation happening in the North and quickly built a loose political coalition with American support. Similar to Kim’s return as a Red Army soldier, Americans were quick to find a leader from the exile community as well; particularly, a respected Korean nationalist and a longtime resident of Washington, DC, Syngman Rhee. A more obvious reason for Rhee’s return was his steady anti-communism, which Americans and Korean conservatives shared. Of course, this Rhee-conservative shotgun alliance, under the newly established Korean Democratic Party (KDP), did not rule the country unchallenged. Since the Peninsula’s southern half had been heavily influenced by leftist labor movements and anti-colonial communism, the KDP’s socially and economically conservative position was a far cry from the progressive political composition of most South Koreans, instead only earning support from a minority of the population. Though Rhee won the election of 1948 by a landslide, leftists claimed the result was fraudulent, as the election was “conducted in an atmosphere of police terror.” As Rhee saw his regime besieged by opposition political forces, primarily the leftists who remained in a now-capitalist Korea, his next course of action became abundantly clear. He began emphasizing and tackling the “communist threat,” which he believed had to be removed from the Peninsula to achieve national unification.

The memorial of unknown freedom fighters at the Seoul National University Hospital

Source: Yong Joo Park

Syngman Rhee speaking on his return to Korea in October 1945

Photo by: Don O'Brien

In October of 1948, the island of Jeju rioted against Rhee’s government, calling it illegitimate and demanding Rhee’s resignation. Rhee sent in an army to suppress the revolt, but the soldiers rebelled too. This event, which came to be known as the Jeju Uprising, ended in heavy fighting between loyal troops and rebel soldiers, and caused the death of 14 thousand more civilians. The rebellion further reinforced Rhee’s antagonism toward communists inhabiting his land, and this fear quickly transformed into furious responses. Guided by the belief that communists were the enemies of the state, Rhee promptly united the right and built a brutally efficient reactionary police state, seeking to achieve the ideological purification of Korea, South of the 38th Parallel.

Cenotaph for the Jeju Uprising Victims at Jungmun

Photo by: Abasaa (あばさー)

His paranoia for a domestic communist uprising was only amplified by the rival government in the North, which he viewed in the same light as his political prisoners. Since the communist government already provided an existential threat to his regime, especially following the withdrawal of US troops from Korea, Rhee felt he needed to employ even more radical actions to guarantee his survival. The red straight pencil line Dean Rusk drew not so long ago, in Rhee’s perception, promised him a communism-free South Korea, which buttressed his belief that, only through eliminating communists within his own borders, could the "health" of the Korean nation be restored. Considering his actions as preemptive measures to deter a “Fifth Column-style” strike, Rhee ordered the arrest of more than 30 thousand suspected “internal enemies” and placed them in Bodo Yeonmaeng camps, whose purpose was to “convert” the communists into “harmless” Korean compatriots. Due to a combination of regime paranoia and a history of Japanese colonial rule, ROK civilians, despite having no ties to Kim’s revolutionary causes, were arbitrarily put into the Bodo Yeonmaeng by the police to fulfill quotas. More than 70% of the Bodo Yeonmaeng members were peasants with no established ideology, arrested simply because Kim’s regime was beloved by North Korean peasants. Mass arrests of real or suspected communist sympathizers in South Korea since the end of 1948 followed a series of propaganda campaigns dehumanizing communists. Rhee had repeatedly used terms such as “exterminating the enemies” and “rooting out the Reds” to justify the White Terror under his rule. Just as the North targeted Christians and industrial capitalists, the ROK relentlessly massacred civilians with suspected ties to leftwing groups, including anti-Japanese guerillas in the colonial period. As a result, the number of civilians affected by Rhee’s policies was enormous.

The memorial of unknown freedom fighters at the Seoul National University Hospital

Source: Yong Joo Park

General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander for Allied Powers, (Left) and Dr. Syngman Rhee, Korea's first President, warmly greet one another upon the General's arrival at Kimpo Air Force Base, at the invitation of President Rhee.

Photo by: Cook

The ROK police was given unrestricted liberty to materialize Rhee’s anti-communist fear. “The time has come to cut out once and for all the cancer of imperialist aggression,” wrote Rhee to US President Harry Truman, “the malignant growth artificially grown within the bosom of our country by world Communism.” As the Korean War broke out in June of 1950, Rhee’s regime was finally pushed to the edge by the communist menace, and the Bodo Yeonmaeng turned from an organization of ideological conversion to an engine of death. Between 200,000 to 300,000 Bodo Yeonmaeng members were dragged into isolated valleys and shot without a trial. The “anti-communist crusade” launched by Rhee, a devout Christian himself, spread rapidly to the countryside, where more civilians worked in the agricultural sector and were hence plagued by the “Red Virus.” Countless innocents, including children, women, and the elderly, were massacred as potential “traitors” working with the leftist guerillas, who had no right to live in Korea. As ROK forces pushed back to the North alongside the US Army, more North Korean civilians became subject to mass atrocities by their southern brothers.

.jpg)

South Korean troops shoot political prisoners near Daegu, South Korea in April of 1951.

Source: U.S. National Archives

Since Rhee was leading a government facing significantly more political opposition and was supported by an ally much further away, mass atrocities under Rhee were more savagely violent than the ones under Kim; these mass executions of suspected communists occurred in a more systematic and organized fashion, usually disguised as methods to safeguard national security or redeem the conquered Northern territories. Rhee’s approach to purify the nations was surprisingly Francoist, aligning perfectly with the Generalissimo's belief:

"The work of pacification and moral redemption must necessarily be undertaken slowly and methodically, otherwise military occupation will serve no purpose."

Mural in Guernica based on a Picasso painting protesting the carpet bombing of Republican territories by Franco’s allies, the Nazi German Luftwaffe “Condor Legion” and the Italian Aviazione Legionaria.

Photo by: Unknown

ROK forces, whom Rhee claimed to be defenders of democratic ethos, reverted to Japanese colonial practices when massacring their way back North alongside the US Army, burning down entire villages of “suspicious civilians” belonging to people of the same ethnicity and nationality. This brutality, however, should not come as surprise, as a considerable glut of Rhee’s forces were drawn from the ranks of the Japanese military, whose colonial expansion had yielded similar stints of violence in the name of anti-communism, which they believed orthogonal to national survival. When the South gained military superiority against the North following the deployment of American troops, the mass killings of communists began relying more on the rhetoric of purification rather than fears of degrading national security. Rhee opposed any peace negotiations and settlements, claiming the only way to pacify the nation was to “march north” and remove the communist threat entirely.

Rhee's Counterattack: March to the Yalu River

Source: Onero Institute

The second difference between Rhee’s and Kim’s practices was that Rhee’s ferocious practices were encouraged by his American allies. Many members of the US Army, influenced by the dominance of McCarthyism on American society, and possessing no more knowledge on Korea than the ruler-toting Dean Rusk, engaged in equally, if not more, brutal massacres against "suspicious civilians." “Kill them all,” ordered the US commanders when a group of South Korean refugees passed their camps in No Gun Ri, a township 160 kilometers southeast of Seoul. The US Army, under the flag of the United Nations, proceeded to open fire, calling in close air support to wipe out hundreds of “gooks” with bullets and incendiary bombs.

Bullet marks at No Gun Ri today.

Photo by: Charles J. Hanley

The No Gun Ri Massacre only represented a small fraction of the atrocities committed by Rhee’s allies, as American air raids amounting to a whopping 32,000 tons of napalm against Korean cities killed an upwards of one million civilians across the duration of the war, without even accounting for the number of deaths caused by the destruction of hydroelectric systems and the collapse of the Peninsula’s rice-based agriculture.

If we keep on tearing the place apart, we can make it a most unpopular affair for the North Koreans. We ought to go right ahead.

B-29 Dropping 1,000lb Bombs Over Korea in August of 1951.

Source: U.S. Air Force

The result of Rhee’s paranoia-fueled politicides, paired with historical ignorance and burgeoning militarism from his American McCarthyist allies, was an amicable response to the arrival of the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army (PVA) by many Korean civilians, who were largely left unharmed by their intervention.

Korean woman carries bag for Chinese solider.

Source: Meng Xianquan (孟憲全)

As the anti-Communist belligerents encountered increased pressure from the North, their disregard for civilian lives only intensified. During the Third Battle of Seoul in January 1951, in which Chinese elite divisions overran ROK and American forces defending the recaptured capital. Persuaded by Rhee’s propaganda that communist troops were merciless executioners, half a million residents of Seoul decided to flee southwards. Since the Hangang River Bridge had been blown up by ROK forces in the First Battle of Seoul, an act that killed hundreds, refugees could only escape the city by sharing two US Army makeshift bridges with ROK officials and soldiers. Brigadier General Charles D. Palmer and his squads of military police even opened fire at civilians when the bridge became increasingly crowded. Matthew Ridgway, the overall commander of the UN Forces at the time, later justified this action citing the “submissiveness” and “resilience” of Korean civilians, which their American counterparts would never have.

Extent of the PVA's southern advance following the Third Battle of Seoul.

Source: Onero Institute

Flight of Refugees Across Wrecked Bridge in Korea (1951 Pulitzer Prize)

Photo by: Max Desfor

Such desperate measures showed how Rhee and his allies had very little regard for the human lives they were supposed to protect when the communist threat was present. The tug-of-war in Korea inflicted mass casualties on all sides, but the ceasefire line, as negotiated by the peace treaty, did not move much from Dean Rusk’s pencil line. The conflict of ideology continues to divide the Korean people to this day, accompanied by countless politicides across decades. As North Korea gradually transformed into a repressive state banning negative press, mass atrocities in South Korea were purposefully concealed by politicians until the 21st century. The Bodo Yeonmaeng Massacre was wrongfully blamed on the KPA, and the two sides accused each other for mass killings in various other incidents. Moreover, the United States, viewing the Korean War as a “wrong war at the wrong place at the wrong time, and with the wrong enemy,” has been reluctant to address its share of the blame. Finally, in 2006, the South Korean Truth and Reconciliation Commission launched investigations into the Bodo Yeonmaeng Massacre, concluding that it was “presumably one of the most massive and organized mass killings in Korea.” The Seoul National University Massacre, on the other hand, is still unacknowledged by the North Korean government.

Lieutenant General Matthew B. Ridgway gives the order to begin dismantling the pontoon bridge after the last of the United Nation Forces evacuated Seoul in January of 1951.

Source: U.S. Army

The 38th Parallel was intended to create a fragile peace between communism and capitalism. Yet, this geometric attempt to tackle a geopolitical problem backfired, as both new Korean regimes became hungry for total control in the name of regime stability. The partitioning line of Korea—splitting six railroad lines, twelve rivers, more than two hundred roads, and countless people with a diversity of views on the Peninsula—fueled decades of political violence among a people that was otherwise united by blood, culture, and history. Furthermore, mass atrocities during the Korean War became the dress rehearsal for other Cold War politicides spawned from similar partitioning plans imposed by external forces, namely the Vietnam War and the Angolan Civil War.

“United We Stand, Divided We Fall.” Ironically, the calligraphy is Syngman Rhee's own handwriting.

Photo by: Rachel So

Seeing Korean War atrocities through the lens of genocide studies and the background of the Cold War has three major implications. First, it shows that mass political killing under the broader context of a civil war, which is not a prima facie covered by the UN Genocide Convention, deserves equal attention for its inadvertent role in dehumanizing and destroying a population. Since regimes in a proxy conflict usually have more powerful backers abroad, it is important to highlight the consensual or even complicit role these backers play. Modifying the international legal framework by taking politicides into account is highly improbable, but nevertheless a worthwhile attempt. Unfortunately, Even if the necessary changes were made, enforcement still constitutes a larger problem.

Second, as scholars and politicians in the West analyze or reference ideology-driven massacres in the Third World, it is often tempting to conclude that bloodthirstiness is linked with the inherent character of the population, rather than the ideological construct imposed upon them. Are Korean leaders, soldiers, and vigilantes more responsible for the atrocities than men such as Dean Rusk’s superiors, who pit them against each other in the first place? As this paper has shown, massacres under both Kim’s and Rhee’s regimes were conscious decisions rooted in the geopolitical reality of a newly partitioned Korean Peninsula; these tragedies, albeit shocking with their scales and brutality, were the continuation of a security dilemma, rather than a byproduct of Korea’s cultural heritage. The same benefit of the doubt, as a result, should be given to other civilizations, currently or historically, suffering from internal instability.

Maps of Korea, Before and After the Korean War

Source: Onero Institute

This realization then illustrates the third implication: external intervention upon a population without responsible or smart decision-making can backfire horribly even if the initial intent was somewhat virtuous. The 38th Parallel was, indeed, successful in preventing the Soviet Red Army from fighting the US Army for disagreements over occupation zones. However, this peace came at the cost of millions of Korean lives, with their homeland, one could argue, permanently divided in hatred and distrust. “I want to see a reunified Korean Peninsula,” declared Lee Hyeon-seo, a North Korean refugee now living in Seoul, “and I believe that the majority of Koreans in both countries want to see Korea become whole again.” The Korean War, as a war of political ideologies and attrition, remains a tragedy for our times as much as it is for Lee’s, as we search to end our inhumane practices against one another, despite the fact that we share much more than we differ.

Flight of Refugees Across Wrecked Bridge in Korea (1951 Pulitzer Prize)

Source: Max Desfor

Display of the Korean Unification Flag during the Christmas Festival at Cheonggyecheon

Photo by: Christian Bolz

Author's Note:

Since the two Koreas use different names to refer to the entire Peninsula (such as “Choson (Morning Calm)” and “Hanguk (Great Country)” in my sources), I used “North Korea” in lieu of “Democratic People's Republic of Korea,” and variations of “Bukhanguk” and “Choson;” “South Korea” in lieu of “Republic of Korea,” and variations of “Namchoson” and “Hanguk.” Please consult A Timeline of Korean History for the context of these names.

Acknowledgements: My thanks go Andrew Ma and Elad Raymond at the Onero Institute for proofreading, illustrating, and providing a platform to young researchers. I also thank Nicolas DeVito, Alejandra Carrillo, Alex Trubey, and Natalie Caloca for their valuable assistance in reviewing and translating. This project would not have been completed without them.

About the Author: Haitong Du is a junior at Tufts University majoring in International Relations and minoring in French. Currently a visiting student at Pembroke College, University of Oxford and a passionate home cook, he is interested in the history, culture, and gastronomy of different civilizations around the world.

At the Onero Institute, we strive to embody both credibility and accessibility in our work. We cite using hyperlinks so that our readers can easily find additional resources and learn more about their topics of interest. Open-access sources are hyperlinked in teal and sources requiring additional access are hyperlinked in gold. If there is a source that you are unable to access for any reason or if you would like more information about a particular source, please reach out to us at engage@oneroinstitute.org.